On December 7th Eduardo organized a dinner for Ricardo and James Vlahos where they got to talk to the survivors about a lot more details. From left to right: Top row: Daniel Fernandez and his wife, Zerbino's wife, Eduardo, Laura his wife, and their son Pedro. Bottom row: Laura

(Roberto's wife), Roberto Canessa, Gustavo Zerbino, Ricardo, Fito Strauch and his wife.

(Roberto's wife), Roberto Canessa, Gustavo Zerbino, Ricardo, Fito Strauch and his wife.

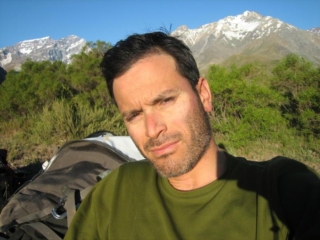

Compare this photo (that James took of me on December 13, 2005, with the famous photo of Nando in the tail with the Adidas bag (the back cover of the Alive hard cover book). If you look carefully you will see that the upper right hand corner matches with this picture. This is the place where the tail was in 1972.

In an upcoming NG article (summer 2006) you will know more about further investigation we did in February 2006 regarding the fate of the tail.

Photo by James Vlahos

In an upcoming NG article (summer 2006) you will know more about further investigation we did in February 2006 regarding the fate of the tail.

Photo by James Vlahos

....and finally...here it is at last...the actual spot on the glacier where the fuselage came to stop after the crash and where the survivors lived for 72 days. Compare this photo to the famous photo of the survivors "sewing the sleeping bag". You will see the background is exactly the same. (you can see the picture on the book or on the survivors page: http://www.viven.com.uy/571/FotosIneditas.asp )

The remains of the fuselage are now buried in the glacier and not visible. To be here on the same day (December 14) as the survivors had been (but 33 years later) looking at this valley completely covered in snow like they did and feeling the cold temperatures that are common at this time of the year really brought home the isolation they must have felt. It was quite challenging to get to this place with these conditions. They were right...a land rescue would have been very difficult.

Photo by James Vlahos

The remains of the fuselage are now buried in the glacier and not visible. To be here on the same day (December 14) as the survivors had been (but 33 years later) looking at this valley completely covered in snow like they did and feeling the cold temperatures that are common at this time of the year really brought home the isolation they must have felt. It was quite challenging to get to this place with these conditions. They were right...a land rescue would have been very difficult.

Photo by James Vlahos

This is the view north from where the plane was.

This picture also matches the one in the book that shows the track made by the fuselage. What neither photo reveals is how steep this slope really is (30-40º). You have to remember this picture is taken looking up! The plane came down between those rocks. The tail went left and the fuselage hit the flat spot where I am standing to take the picture.

This picture also matches the one in the book that shows the track made by the fuselage. What neither photo reveals is how steep this slope really is (30-40º). You have to remember this picture is taken looking up! The plane came down between those rocks. The tail went left and the fuselage hit the flat spot where I am standing to take the picture.

...and this is the view West and the escape route! You are looking at almost 3000 vertical feet. The view from this close undermines the difficulty of climbing that wall. The survivors thought it would take them one day to get to the top. In fact it took them 3 days! We were forced to do it in one day (the day after this picture was taken) due to rock fall, ice fall, and avalanche danger, and it was brutal! Also, as you can see, the slope was so loaded with snow that there would have been nowhere to camp safely (digging a snow plataform into an avalanche prone slope is not a good idea).

Climbing the headwall. In order to avoid the crevasse in front of me I had to go right and expose myself and the team by going under that hanging glacier. The debris of yesterday's avalanche is visible on the picture.

Unfortunately that hanging glacier was losing car size chunks of ice almost everyday and at all times of the day and night, so it was impossible to

predict when the next one would come. This was pretty much a game of russian roulette.

Photo by James Vlahos

Unfortunately that hanging glacier was losing car size chunks of ice almost everyday and at all times of the day and night, so it was impossible to

predict when the next one would come. This was pretty much a game of russian roulette.

Photo by James Vlahos

This is probably the view that Roberto Canessa was looking at in 1972 when he saw the road. As you can see on this picture, the road is visible at the foot of El Sosneado (the big mountain in the background), though barely. Roberto was right, though it's understandable why Nando didn't want to go back.

Here is a composite of three pictures to show their view west when they finally reached the saddle (or the "top of the mountain" as they refer to it in the book). Visible are the two peaks without snow that they hoped would mark the end of the Andes in Chile. On the forefront you can see the gullies we had to descend to continue our trek to Chile. I am standing on the crest of the Andes at 14,800', the international border between Argentina and Chile.

The view South reveals this summit (15,400'), which is the peak I climbed on February 2005 (see Discovery) to get a view of what Nando and Roberto had seen to the west. My route of ascent in February was via the ridge on the left side. This picture was taken from the top of a 15,000 ft summit which I climbed the same morning. Visible in the picture is our camp on the saddle (and James or Mario standing next to the tent). To the right is Chile, to the left Argentina.

This is the gulley we followed. One of my concerns was that after 34 years of erosion (which is extreme in this part of the Andes) we would be stopped by a cliff. With the quality of rock being so rotten it could be imposible to set up a rappel and we would have to climb back up and try different routes until one worked.

This is El Brujo. Nando and Roberto saw the sun illuminate this peak until 9 pm. This gave them great hope that the next valley was open to the west, since apparently no mountains were in the way to block the sun. This picture was taken a few minutes before 9 pm on December 16, 2005.

Photo by James Vlahos

Photo by James Vlahos

At one point a rock dislodged under my foot and I went down. My pack crushed me against rocks that hit my sternum and cut my forearm. A hematoma formed instantly on my arm which made it look like a compound fracture; I was very relieved to see that it was just a cut! A compund fracture, days away from any help, can be a very serious matter, if not fatal.

December 18,2005 The challenge of this day and the next one are the hardest to convey. We no longer had dangers of avalanches, crevasses or technical terrain; it was simply a physical challenge to cover miles and miles with heavy packs, heat, and direct sun over terrain that's tricky to walk on.

Photo by James Vlahos

Photo by James Vlahos

The heavy vegetation made it impossible for us to continue. The only option I found was to follow herd paths (that we were now encountering along with a few cows grazing but no humans) that climbed up more than 1500 vertical feet above the river and went above this ridge line that would eventually drop us into Los Maitenes. It was very discouraging to have to climb yet another mountain when we were so close to our destination.

At last on December 20, 2005 our crossing of the Andes on foot ended when we reached this road and this vehicle. We had a very different

experience of San Fernando, Chile, than the survivors. While the survivors were welcomed like heroes (the rest of the survivors back on the glacier were rescued by helicopters), we were greeted like illegal criminals. As we reported to the local authorities to have our passports stamped with the proper entry stamp we were practically detained. That entry stamp was essential to leave the country the next day, otherwise we would be detained at the airport and arrested.

Photo by James Vlahos

experience of San Fernando, Chile, than the survivors. While the survivors were welcomed like heroes (the rest of the survivors back on the glacier were rescued by helicopters), we were greeted like illegal criminals. As we reported to the local authorities to have our passports stamped with the proper entry stamp we were practically detained. That entry stamp was essential to leave the country the next day, otherwise we would be detained at the airport and arrested.

Photo by James Vlahos