NG Expedition II

Read the Story After the Gallery

Return to the Andes

by James Vlahos July 17,2006

On December 22, 1972, Eduardo Strauch heard the most beautiful sound in his life. It was a clattering roar that reverberated between the high Andean peaks, raced across the glaciers below, and penetrated the crumpled airplane fuselage that lay in the bottom of the valley like a discarded toy. Strauch and 13 other emaciated boys rushed from the wreck of Fairchild 571 and frantically scanned the sky. The noise was everywhere at once but nowhere in particular. Then, rising from the east, they saw two helicopters. Seventy-two days after a plane carrying a Uruguayan rugby team and its supporters had crashed en route to a match in Chile—72 days in which the survivors faced bitter cold and a lethal avalanche and were forced to eat the bodies of the dead passengers to survive—rescuers had finally arrived.

Ten days earlier, Roberto Canessa and Nando Parrado had set out on a dangerous trek across the Andes in search of help. The survivors left behind were hopeful at first then increasingly desperate as the days passed with no word. Several of the boys were near death, and the others prepared to send out another search party. But this plan was joyfully forgotten on the morning of the 22nd. Eduardo and his two cousins, Fito Strauch and Daniel Fernandez, were crouched outside the plane listening to a tiny transistor radio. Trying to pull in a station, they caught the names “Canessa” and “Parrado” in the static

but thought that they were mistaken. Then they heard the rich, beautiful strains of“Ave Maria” and knew that Canessa and Parrado had succeeded.

The survivors, all young men between the ages of 16 and 25, screamed and cheered. Fito Strauch grabbed a fire extinguisher and blasted them with white foam, shouting “avalanche!” Eduardo Strauch felt happiness gushing from his pores like it was liquid. When the rescue helicopters of the Chilean Air Force arrived, he accidentally knocked over one of the weakest boys, Roy Harley, in his rush forward. Harley lay helplessly on his back like a turtle while Strauch climbed aboard one of the helicopters.

He worried briefly about what the rescuers must think. The area around the Fairchild was strewn with bones, pieces of meat, and whole corpses thinly covered with snow. Strauch could imagine how horrific the scene must look to the rescue crew. He quickly pushed these concerns from his mind. Ten days into the ordeal, lacking food and facing starvation, each member of the group had agreed that if he died, the others could use his body for sustenance.

Survival would not have been possible otherwise, and there was no hiding from their decision now.

As the rotor blades raced for takeoff, Strauch clutched a small bag tightly in his lap. It contained an item that had comforted him profoundly during the ordeal—a red-lettered sign from the plane that read “EXIT.” The helicopter lifted into the air, and he was filled with nostalgia as he watched the Fairchild—oppressive prison, lifesaving shelter, home—become a speck in a sea of whiteness. This, he was certain, was the last time he would see the valley. He couldn’t stop looking until it had disappeared from view.

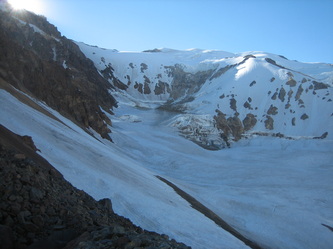

Strauch was wrong. In February this year, on a blustery day with tiny pellets of snow being flung through the air, his feet once again touched the ground of El Valle de las Lágrimas, the “valley of tears.” He wore a harness and was walking down a snowy mountainside onto the glacier spread across the valley floor. Twenty feet of rope connected him to Ricardo Peña, a Boulder, Colorado-based guide who runs a company called Alpine Expeditions and is one of the world’s leading experts on the Andean survivors. Behind Strauch, linked by another 20 feet of rope, I followed carefully, ready with my ice ax to drop into self-arrest if Strauch punched through into a crevasse. He survived a plane crash and an avalanche, I found myself thinking. Do NOT get him killed now.

Peña stopped after every couple of steps and used a pole to probe for hidden crevasses like a dentist hunting for cavities. Finally he stopped on a flat spot and nodded. He reeled us in to him, always keeping the rope taut. Strauch’s jaw was clenched. Glassy-eyed, he looked around slowly: at the 3,000-foot gully that the Fairchild hurtled down after crashing. At El Sosneado, the 18,000-foot volcano that appeared to block the survivors’ escape route to the east. And at a formidable, crevasse-riven headwall of snow to the west—the one that Parrado and Canessa had ultimately scaled on their way to find help. “This is it,” Strauch said. “This was our home for 72 days.”

Over the decades since the rescue, many of the survivors have made summertime treks to the small memorial and gravesite located at the eastern end of Valle de las Lágrimas. Due to the difficulty of glacier travel, however, none of them has returned to the original site of the Fairchild (the plane has since been swept away and buried by avalanches). Strauch was the very first to come home.

Peña and I, with support from the National Geographic Society Expeditions Council, were seeking new information about the crash and the struggle of the survivors. In December 2005 the two of us, along with Argentinean guide Mario Perez, were the first to retrace the escape trek of Canessa and Parrado (see “Alive: Then & Now,” Adventure, April 2006). Now we had returned for what amounted to a high-altitude treasure hunt.

Like the sea floor where the Titanic went down, El Valle de las Lágrimas is dotted with artifacts, each representing part of the drama that unfolded here. Many are in known locations, some are lost, and all are in danger—from looters and even more, from the relentless abuse of wind, snow, and water. Strauch and some of the other survivors want to collect these historic items and preserve them in a museum operated by their nonprofit organization, Fundación Viven. To aid the effort, Peña and I organized a weeklong expedition to take stock of the known items and to climb through treacherous terrain on a search for lost ones. The locations would be recorded with GPS waypoints. Sometimes we would have the assistance of Strauch and a small support team, but most of the exploration would be done on our own.

For Strauch, the expedition was more than simply a hunt for artifacts; it was also a search for memories that had been dulled by time. Standing at the Fairchild site, Strauch pointed to a swath of snow just uphill from us. “We made a cross in the snow from luggage to help the search planes see us, but it was impossible to see anything from the air,” he says. “Not the cross, not the fuselage, not anything.” Strauch then gestured to the mountain that the Fairchild had slid down. During the crash a boy named Carlos Valeta had been expelled from the back of the plane. Not seriously injured but deeply in shock, he stumbled down the mountain, oblivious to the shouts of the other survivors. As they watched helplessly, Valeta plunged into a crevasse.“We

never saw him again,” Strauch said.

Before the helicopters whisked them away, the survivors had thought that their story would be of limited interest to the outside world. Perhaps there would be a few articles in the Uruguayan press and a presentation at a local theater, and then the whole terrible experience would just go away. In hindsight, this seems humorously naive. The boys’ ordeal lasted less than three months, but they would spend the rest of their lives being The Survivors.

Here is what this is like:

As a survivor, you belong to a giant family.

All but one of you lives in Uruguay, many in the same neighborhood of Montevideo where everyone grew up. Small groups of you see each other weekly, and all 16 gather annually on December 22 to commemorate the rescue. You help manage the Old Christians Rugby Club—the same one that sponsored the deadly journey in 1972—and in 2002, many of you played a match in Chile in remembrance of the one missed due to the crash. You have children, maybe even grandchildren, forming an extended clan some one hundred members strong. “We are closer than brothers, even than lovers,” as one of you puts it.

You are at the center of a media circus.

It began the moment you returned to civilization and has never let up entirely since, with waves of articles and television specials. Piers Paul Read’s best-selling book, Alive, has been read by tens of millions of people worldwide and was made into a Hollywood movie; earlier this year, Nando Parrado’s Miracle

in the Andes cracked the top ten of the New York Times best-seller list. Your story has been retold in avant-garde theater and on Broadway. This spring, it was also a tawdry reality TV show featuring D-list British celebrities who dined on raw beef and “suffered.” As survivor Moncho Sabella puts it: “I sometimes want to say to the people who package us for popular consumption, ‘We ate the dead. You eat the living.’”

You are a success.

You are Roberto Canessa, highly regarded pediatric cardiologist and 1994 third party candidate for president of Uruguay. You are Coche Inciarte, one of the country’s most productive dairy farmers and respected painters. You are Nando Parrado—author; host of adventure-sports television shows; and most successful of the several survivors who work the lecture circuit, with talks given to Fortune 500 companies at $30,000 a pop.

You are a hero, a saint, a rock star, a cannibal.

You are Eduardo Strauch.

Though you played a pivotal leadership role on the mountain, you never sought the media spotlight. You married a beautiful woman, became an architect in Montevideo, and raised five children. Over the years, as the story has been retold ad infinitum—as survivorship has become like being a stockholder in Survivors, Inc.—you have begun to feel estranged from your own history. The narrative had become secondhand, surreal, and the Andes seemed far off.

It was Ricardo Peña, in many ways, who called you back. In 2005, he discovered your wallet and passport, which had lain at 14,000 feet in the snow since the day the Fairchild smashed into the mountain. When you held these items in your hands again, they felt like old friends. Peña fueled your new interest in speaking publicly about the tragedy, and now you, too, give lectures in Latin America and the United States. It was Peña who proposed that you return to the site of the Fairchild, first in 2006 and again in February 2007 with guided clients who want to hear the story of the survivors in the place where it happened.

You could go back to the Andes and see the valley, Peña said. You could touch artifacts and remember.

A few days after we took Strauch onto the glacier, I stood on a high rock outcrop beside Peña, who was studying a photo clutched in his hands. “This has to be it,” he said. “I’m sure this is the spot.”

The picture, taken by one of the survivors in 1972, showed the Fairchild’s tail. In the crash, it had been ripped from the rest of the plane, and the survivors didn’t know what had become of it. First they searched the slopes above the plane. Then, on a futile search for an escape route in mid November, Canessa, Parrado, and Antonio Vizintín stumbled upon the tail about a mile east of the fuselage.

To the threesome, the tail was equal parts lifesaving supply cache and Andean Club Med. Inside were crackers, a bottle of rum, and cigarettes, as well as extra clothes, some medicine, and a two-way radio they hoped they could get to work. Buoyed by the vital discovery, the boys built a fire inside the tail and stayed up late reading comic books.

In recent years, a couple of people have claimed that they spotted what might be the tail from far off in the valley, but nobody has actually found it. Doing so was a primary objective for Peña and me. Looking at the photo, though, we realized one thing: The tail wasn’t where it was in 1972. “I think we need to go down this way,” Peña said, pointing into a steep, rocky ravine below the outcrop.

The glacier had ended, and an icy river gushed through the gorge. There was only one direction for objects to travel—down. First we found one of the plane’s seat cushions, which the survivors had strapped onto their feet to use as snowshoes. It might have been abandoned here on the expedition to the tail. Then we spotted a piece of metal on a boulder-strewn slope above the water. It was the door from the tail, almost fully intact.

We knew we were close, but the route had stranded us on a peninsula of rock between converging river channels. The rapids were massive, and there was no question of crossing. Instead, we retreated up the ravine, crossed to the northern edge of the valley, and headed back down, this time steering wide of the braided river channels in the middle. Only after all of them converged did we reach the river’s left bank. And that’s where we saw it, unmistakably: The Fairchild’s lost tail.

Huge sheets of plane siding lined a 30-foot stretch of riverbank, partially buried by rocks. Electrical and hydraulic cables protruded upward. I got down on my knees and peered into the dark, sunken interior where Canessa, Parrado, and Vizintín had taken such welcome shelter. It was thrilling to find such an important artifact, but depressing to see it in such sorry shape. Water and rocks had taken their toll. I recorded a GPS waypoint and hoped that the survivors’ foundation could recover the tail and reconstruct it before it was destroyed completely.

There was little time to linger. Though we were in the middle of the Andean summer, the weather had been foggy and cold all day. Afternoon was upon us, and as we started the trip back to camp, a heavy snow began to fall.

Canessa, Parrado, and Vizintín made a second trip to the tail along with Harley. The first three had always been among the strongest boys and were being given extra rations in preparation for the escape trek to the west. Harley wasn’t getting additional food but had been brought along because he knew a little about electronics and the group thought he might be able to fix the two-way radio.

Despite several days of frustrating labor, the effort failed. And on the return trip, a blizzard struck them, too. Harley, weaker than the other three, straggled behind and finally fell in a heap in the snow. In Miracle in the Andes, Parrado recounts that he tried to encourage Harley to keep moving. When his

friend refused, Parrado got mad and left him for dead. But after a few steps forward, he returned. He kicked and punched Harley as hard as he could. He

called him a bastard, a whore. Harley arose, and Parrado pushed and towed him uphill until they made it to the Fairchild.

Peña and I made it back to camp at dusk after a harrowing clifftop crossing above the river and near-whiteout conditions. We grabbed cheese, crackers and salami from the supply tent, and then each headed to our own tents to wait out the blizzard. It lasted a day and a half. The snow piled up in drifts so deep that I periodically had to beat the walls of the tent to keep them from collapsing under the weight. On the mountain slopes high above, I heard the roar of avalanches.

Seventeen days after the crash, on the evening of October 29, Eduardo Strauch laid down on the floor of the Fairchild and tried to sleep. He was squeezed between his cousin Fito and his best friend, Marcelo Perez.

Strauch had known Perez for nearly 20 years. They attended the same schools, rode horses, went to the beach, took vacations, and double-dated together. Perez was the captain of the rugby team, and in the wake of the crash, he assumed leadership of the survivors. Strauch, however, was worried about his friend. On the tenth day, the survivors had heard over the transistor radio that the air force search for them had been canceled. Perez was completely demoralized and lost the ability to lead.

As they lay next to each other that night, Strauch heard a deafening noise. The slopes above the Fairchild had unleashed an enormous avalanche and within seconds it filled the Fairchild with snow. Buried completely in the icy pack, Strauch squirmed desperately but found he couldn’t move.

In classic fashion, he began to witness countless scenes from his life. He stopped struggling and felt at peace, for he was being called to a marvelous place where he could leave all of his suffering behind.“I’m dead,” he thought. At that moment, Fito, who had freed himself and was digging frantically to save his cousin, broke through. A huge breath of oxygen filled Eduardo’s lungs. He was alive again.

Strauch dug desperately with the others but they weren’t in time to save all of the boys. Eight people perished under the snow, and Marcelo Perez was one of them.

Today, the remains of some of the people who died in the Andes are buried at the memorial site, which sits on a low ridge and consists of several piles of exposed rocks topped by rusting iron crosses. Our camp was in a ravine nearby, and one sunny morning after breakfast—this was before the blizzard hit—Strauch paid his respects.

Over the years, visitors have left mementos behind, and when plane parts turn up in the valley, people often pick them up and deposit them by the crosses. Individually people have meant well, but the collective result is a mess. Strauch worried that the site looked less like a memorial than it did like a dump.

He had conferred with some of the other survivors, and they decided that the memorial should be better organized. Strauch began to remove heavy, rusting plane parts from the main memorial mound so that it would have only plaques, flowers and the cross on top. He created a separate pile for the plane artifacts, moving oxygen bottles, remnants of the cockpit electronics, small gauges, and twisted scraps of metal. Peña and I helped him move a panel of the fuselage surrounding a still-intact window and a heavy piece of the plane’s landing gear.

By midday, the sun was directly overhead and the heat was fierce. In the thin air, I became winded and stopped to rest. Peña took a break, too. But Strauch, scarcely uttering word, worked ceaselessly. He called us over to look at a set of parts that he had arranged on the ground: seatback upholstery, a tray table, and an armrest complete with ashtray, arranged perfectly to simulate a seat in the plane.

To Strauch, each artifact around us told a story of decisions they made to stay alive. The loss of Perez left a leadership void, and in its place rose the triumvirate of the cousins, Eduardo, Fito, and Daniel, who devised many of the strategies critical to their lives. The seat covers were used as blankets, a small barrier against the Andean winter. Sheets of metal from within the seats worked as bowls to melt snow; fuel bottles were used to store the water. I spotted a wedge of plastic that was filed down to form a crude knife. More likely than not it was used by Eduardo himself to cut flesh from the dead, for the cousins handled the daily rendering and distribution of food.

“We began to form a small society out of nothing and had to adopt a whole new set of values, to abandon all of the old ways of living and substitute them with something that was more fit for survival,” Strauch says in his lectures. “Over time, we got the new society to work fluidly, taking care of the everyday jobs needed to survive.”

A search and rescue crew cleaned up the valley in early 1973 but was unable to adequately bury human remains in the rocky ground. Squatting over the grave, Strauch spotted small body parts, some with withered flesh still attached, including a five-inch column of human spine. He also saw a delicate chain and medallion and picked it up carefully. “This belonged to Marcelo,” he said.

For two decades after the tragedy, Perez’s family refused to speak with Strauch. The memories were too painful. But Strauch never forgot his best friend. He believes that Perez assumed too much responsibility for the survivors’ horror—the flight across the Andes to play a rugby match had been his idea. The avalanche may have killed him, but his spirit was already dead. “Marcelo died right next to me,” Strauch said. “I never felt him move or resist.”

A couple of days after the storm Peña and I set out to climb the mountain above the original fuselage site. If we reached the top, a climb of a few thousand vertical feet to a 15,000-foot saddle, we would be two of the very few people to ever see the exact place where the Fairchild crashed.We began at dawn. At the foot of the mountain, dusted with fine powder snow, was a grey tail wing. It was in excellent condition and looked like it had been deposited there only hours earlier, not decades.

As we moved from broad slopes into a narrow couloirs, the sun began to melt the snow, and rocks, released from the ice above, came tumbling down. A couple of times I had to jump at the last second to avoid being hit. At midday we reached a junction where the mountain face divided into two gullies. Conventional wisdom holds that the Fairchild plunged toboggan-like down the gully to the left, but Peña believed otherwise. On a scouting expedition in 2005, he saw plane parts in the steeper, narrower gully to the right, and formed the theory that the plane had come down that way instead, which would have made for an even wilder, more death-defying ride down. Further up was where he found Strauch’s wallet and passport.

Hoping to spot more evidence, we headed up the right-hand chute. The surface had melted, refrozen and melted again; that process, coupled with the effects of wind, had formed treacherous penitentes, triangles of ice that rose chest high on the 45-degree slope.

On the way up, sure enough, we saw plane parts: a triangular fiberglass panel ripped violently from the fuselage, a metal brace, black electrical wire. All of these offered confirmation for Peña’s theory. “It’s very hard to imagine they survived sliding down this,” he said, looking down the precipitous slope at massive outcrops of rock that flanked the chute. “A little bit more to the left or right and they would have been history.”

Peña is in the innermost circle of the cult of the Andes survivors, an unofficial worldwide fan club of people who have read the Alive book and watched the movie dozens of times; who can identify each of the survivors from their picture; who know trivia such as the exact time that the Fairchild took off on its final flight. The club is not without its oddball fringe—there are reportedly fans who have purchased Old Christians rugby jerseys and get together to play Alive-themed role-playing games—but the influence of the Andes survivors is largely quite positive. To this day, the survivors receive fan letters and emails from around the world, sometimes a dozen or more per week. They come from cancer patients, sexual abuse survivors, and ordinary people. If there’s a common theme to the correspondence, it is that people feel that their own troubles are manageable in comparison to those faced by the survivors.

After several hours of climbing, we emerged from the gully atop a barren, windswept ridge. A set of crumbly rock pinnacles rose to the south, and the ridge built a few hundred more vertical feet to the north. Otherwise we were standing on the highest point around. Spanning Argentina and Chile, the snow-capped Andes spread out before us. “I think the pilot aimed at the lowest point of the saddle and tried to overcome it,” Peña said. A few feet higher and none of the tragedy would have unfolded below.

On Strauch’s final day in the Andes, we sat out by the tents. We used our sleeping pads makeshift seats on the snow and opened a few precious cans of beer. The weather was balmy. To the east, the massif of El Sosneado glowed red with the light of the setting sun. “One afternoon in December we saw two huge condors flying above us,” Strauch said. “They were the only living creatures besides ourselves that we saw in 72 days.” The boys felt forgotten by the world and the birds gave them a sense of companionship. “That’s the degree of loneliness we had, even though we knew they were just waiting for us to die.”

Like most of the survivors, Strauch discovered God in the Andes. It was not the God he had heard about in church, not an omnipotent being in the sky, watching all, taking wise action. God, he realized, was less powerful but more diffuse—He was the snow, the sun, the mountain.

After the rescue, many people in Latin America regarded the boys as saints; their salvation was thought to be divinely ordained. But that didn’t fit with Strauch’s new religious views. He knew that among the group of survivors there were optimists who waited blindly for rescue, pessimists who lost hope, and realists like him, his cousins, and Parrado and Canessa. They stayed logical and formed plans.

God didn’t save the survivors. They saved themselves.

And now Strauch was back. He once said that for years after the rescue, his mind was still 60 percent in the Andes; to this day he was always 20 percent there. Initially thought that he wanted to be cured of those final remnants, to be rid of the Andes for good. But the opposite is the case.

On so many afternoons, Strauch said, this is exactly what he and the other survivors did: They sat watching El Sosneado at sunset. In the Andes, the survivors were free of society’s selfishness and materialism. Money was something you used to start a fire; pleasure came in simple interludes like this one. “I actually lived in the Andes some incredible moments of happiness,” he said. “There were meditative states and a sense of freedom that I’ve never had

since.”